Figure A

Image Title: Fashion Doll (Pandora) with Accessories

Museum: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Place of origin: England, Great Britain

Date: 1755-1760

Artist/Maker: Unknown

Museum number: T.90 to V-1980

URL: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O100708/fashion-doll-with-unknown/

“A tirewoman in Paris send to London a doll completely accoutered to shew the new mode…At the sight of this pageant (O how wonderously pretty!) off goes the present head-dress of every lady in the realm, to make room for the exact similitude and pattern of the coiffure of the newly-arrived, pretty, little, dear, charming stranger from France.” (Governor William Livingston of New Jersey, “Homespun,”1791)

During the eighteenth century Pandoras or Fashion Dolls were sent by dressmakers all over Europe and America to exhibit the latest fashions and encourage women of society to purchase their goods. The Fashion Pandora shown above was produced in England between 1755-1760 with the aim of promoting this form of elaborate court dress. This blog post shall explore the material culture of this Pandora suggesting that she reflects a time in which consumer goods and fashion were becoming important ideals in society.

The Pandora reflects a period of seismic change in the patterns of consumer spending in England. Neil McKendrick argues that there was a “consumer revolution” as more people than “any previous society in human history [were] able to enjoy the pleasures of buying consumer goods.” The idea of being in ‘fashion’ perpetuated the commercialization of society as it provided an incentive to buy new goods in order to keep up with the times. The upper classes in particular sought more and more luxury goods in order to maintain an exclusivity that was seemingly being lessened by the greater access to consumer goods from all classes (McKendrick, 9-11). Reflecting McKendrick’s notion of the need for exclusivity, the Pandora is made from opulent fabrics such as silk, satin and lace. It also uses a myriad of techniques of production including braiding on the petticoat, and a quilting design on the under-petticoat (V&A). Sartorially, the level of craftsmanship and expensive nature of the fabric reveals the importance of luxury to the fashionable ladies of the eighteenth century.

Image Title: Doll’s Pocket

Museum: Victoria and Albert

Place of origin:

London, England (made)

Date: 1690-1700 (made)

Artist/Maker: Unknown (production)

Museum number: T.846C-1974

URL: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O82500/dolls-pocket-unknown/

Notes: Pandoras often demonstrated every layer of dress including undergarments. In this example, the Pandora has a pocket hidden under her petticoat. This reveals that there was some element of practicality to dress not just aesthetic value during this time.

For women of society the Pandora doll symbolized the opportunity to make new purchases and gain the prestige and satisfaction of owning the latest form of dress. In Governor William Livingston of New Jersey’s discussion of the Homespun Movement in America (which aimed to promote American cloth) he describes the excitement that women felt in receiving these dolls in their homes, immediately mimicking the forms of fashion that she displayed (Governor Livingston, Homespun, 1791). Indeed, in a eulogy for the Duchess of Devonshire published in the Belle Assemblée one of the things that the author most admired most about her, and that gave her such an elated position in courtly society, was that she was “fashionable” and gave her name to many articles of clothing (Belle Assemblée, 123-4). Fashion was thus intimately connected with status, and the Pandora was considered as an important gateway to obtaining this prestige.

Demonstrating this material culture of the Fashion Doll, the satirical image shown in Figure B depicts a girl holding a doll dressed in similar attire to the women of the picture, which may be a Pandora. It could be suggested that all of the women shown in the image are mirroring the fashion of the little doll, particularly as the girl is set apart from the other women as if she and the doll are watching over them. The Pandoras thus symbolized more than just for a material representation of what clothes could be made for the women, but the status these clothes could potentially offer them.

Figure B

Title: Frailties of fashion

Museum: British Museum

Place of origin: London, England (published)

Date: 1793

Author: Print made by: Isaac Cruikshank; Published by: S W Fores

Museum Number: 1868,0808.6292

URL:http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1654172&partId=1&searchText=fashion+doll&page=1

Notes: Often Pandoras would be given to children to play with as toys after they had been viewed.

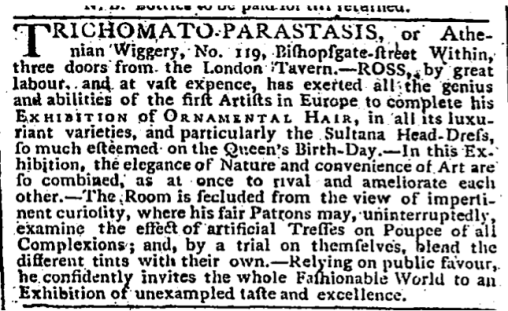

For the distributors of the dolls themselves, the Pandora represented the chance for greater business and personal prosperity by acquiring new orders. As such, the Pandora doll can be viewed as an early form of promotion or marketing. In an advertisement listed in a London newspaper in 1799 a wig-maker invited “the whole Fashionable World to an Exhibition of unexampled taste and excellence” where they could examine the wigs on “poupee [French for doll] of all complexions” (Morning Herald, February 12 1799) (Figure C). The dolls or mannequins in this example were a medium for allowing women to envisage what the wigs would look like in practice, and they seem to have encouraged people to come into the store. Not only does the Pandora demonstrate, therefore, the commercialization of sales but also the way in which strategic forms of promotion could encourage people to consider goods ‘fashionable’ and desirable.

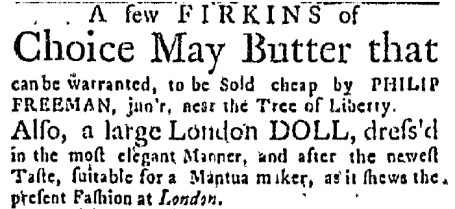

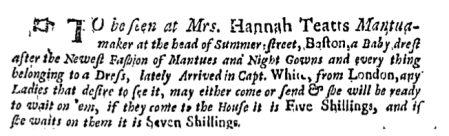

Interestingly, the Pandora played a crucial role in spreading European ideals of fashion and consumerism to the colonies. Governor Livingston notes that old clothes were abandoned half worn once dolls from France and England arrived in America “upon the pain and penalty of being old fashioned” (Governor Livingston, “Homespun,” 1791). Clearly for the women of the colonies the Pandora represented the chance to obtain the status that came with being a ‘women of fashion’ even though they did not happen to live in Paris or London. By examining contemporary newspapers this desire to copy European ideals of style is evident. An advertisement in a Boston newspaper in 1766 noted that there was a “large London doll, drefs’d in the most elegant Manner” for sale (The Massachusetts Gazette, 2 October 1766) (Figure D). Another advertisement noted that a Mantua-Maker had recently received a doll from London that could be viewed for 5 shillings in the store and 7 shillings if it was delivered to them (New England Weekly Journal, 9 July 1733) (Figure E). The popularity of Pandoras in America not only shows that European tailors were able to obtain an international clientele, but also that the women in the colonies still ultimately wanted European forms of dress. Despite the aims of movements such as Homespun ‘women of fashion’ still coveted the power and class symbols that were intrinsic to European attire. This consumerist desire was satisfied by the travelling doll.

The Pandora therefore reflects an age in which there was a growing emphasis on consumer goods from a social and economic perspective. The “pretty, little, dear, charming stranger” (Governor Livingston, “Homespun”) brought more than simply potential patterns of dress to women. For the dedicated followers of fashion, she brought the chance to be at the forefront of style during a time when this was a very important ideal.

Figure C

Article Type: Classified ads.

Newspaper: Morning Herald

Place of origin: (London, England)

Date: 2-12-1799

Issue: 5742 Page: Unknown

Figure D

Article Type: Advertisement

Paper: Boston News-Letter, published as the Massachusetts Gazette.

Date: 10-02-1766

Issue: 3287 Page: 4

Place of origin: Boston, Massachusetts

Figure E

Article Type: Advertisement

Paper: New-England Weekly Journal, published as New England Weekly Journal.

Date: 07-09-1733

Place of origin: Boston, Massachusetts

Issue: CCCXXIX Page: 2

Bibliography

Chapters in books

McKendrick, Neil. “The Commercial Revolution of Eighteenth-Century England.” In The Birth of Consumer Society: The Commercialization of Eighteenth-Century England, 9-33. London: Europa, 1982.

Articles/Advertisements

Advertisement. [No Headline]. London Morning Herald, February 12, 1799. Accessed February 28,2014.http://find.galegroup.com/bncn/retrieve.do?sgHitCountType=None&sort=DateAscend&prodId=BBCN&tabID=T012&subjectParam=Locale%2528en%252C%252C%2529%253AFQE%253D%2528tx%252CNone%252C6%2529poupee%2524&resultListType=RESULT_LIST&searchId=R1&displaySubject=&searchType=BasicSearchForm¤tPosition=6&qrySerId=Locale%28en%2C%2C%29%3AFQE%3D%28tx%2CNone%2C6%29poupee%24&retrieveFormat=MULTIPAGE_DOCUMENT&subjectAction=DISPLAY_SUBJECTS&inPS=true&userGroupName=uclosangeles&sgCurrentPosition=0&contentSet=LTO&&docId=&docLevel=FASCIMILE&workId=&relevancePageBatch=Z2000899931&contentSet=UBER2&callistoContentSet=UBER2&docPage=article&hilite=y.

Advertisement. [No Headline]. New England Weekly Journal, September 7, 1733. Accessed February 28, 2014. http://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/HistArchive?p_theme=ahnpdoc&p_action=doc&p_product=EANX&p_nbid=J51X4DPJMTM5NDIzOTg5NC40Nzc2MTU6MToxMDoxMjguOTcuMC4w&f_docref=image/v2:108C1BB941096180@EANX-108C9BB06B0E6660@2354215-108C9BB0AA8FBC98@1-108C9BB1214CCBA8@&p_docref=image/v2:108C1BB941096180@EANX-108C9BB06B0E6660@2354215-108C9BB0AA8FBC98@1-108C9BB1214CCBA8@&p_docnum=-1.

Advertisement. [No Headline]. The Massachusetts Gazette, February 2, 1766. Accessed February 28, 2014. http://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/HistArchive?p_theme=ahnpdoc&p_action=doc&p_product=WHNPX&p_nbid=L59V55BRMTM5NDIzOTc2My42MTY3MjQ6MToxMDoxMjguOTcuMC4w&f_docref=image/v2:1036CD221971FE08@WHNPX-105B5726775957D8@2366353-105B5726E746A432@3-105B5727C068AA57@&p_docref=image/v2:1036CD221971FE08@WHNPX-105B5726775957D8@2366353-105B5726E746A432@3-105B5727C068AA57@&p_docnum=-1.

Eulogy. “The Duchess of Devonshire.” Belle Assemblée, April, 1806.

Livingston, William. “From the American Museum. Homespun.” Massachusetts Spy, September 1 1791. Accessed February 28, 2014. http://docs.newsbank.com/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info:sid/iw.newsbank.com:WHNPX&rft_val_format=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&rft_dat=102F3F6113484977&svc_dat=HistArchive:ahnpdoc&req_dat=0D6884C8DA6CD5B5.

Images

“Doll’s Pocket.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed February, 22 2014, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O82500/dolls-pocket-unknown/

“Frailties of Fashion.” British Museum. Accessed February, 22, 2014, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=1654172&partId=1&searchText=fashion+doll&page=1

“Fashion Doll with accessories.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed February, 22 2014, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O100708/fashion-doll-with-unknown/