Published by John Vincent De Toro

“Errors which are introduced by Luxury, suffer’d thro’ Ignorance, and supported by being fashionable. [The Statesman] would soon have condemned the exorbitant Use of Tea… But the present Age has other Considerations; Tea pays too great a Duty, and supports too many Coaches, not to be preferr’d to the Health of the Publick: Tea has too great Interest to be prohibited.”

— James Lacy, “An Essay on the Nature, Use, and Abuse, of Tea, in a Letter to a Lady.”

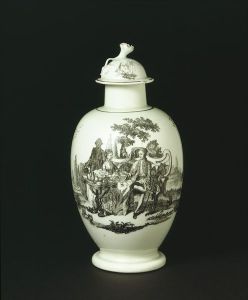

The artifact presented here is a beautifully expressive Tea Canister from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection, museum number 1448&A-1853, produced ca. 1768. This piece is made from soft-paste porcelain material with two transfer-printed in black enamel decorations, engraved by Robert Hancock for Royal Worcester. Initially reserved for the wealthy, these canisters, or caddies, were used to store tea and, as tea prices dropped in the eighteenth-century, became much more bulbous and spacious.

It is worth noting that, despite being a widely-proliferated complementary good vis-à-vis tea itself–evident in large collections held by museums alongside other tea-service works, written sources directly related to this artifact seldom appear which straightforwardly discuss its fashionable or material importance. However, the historical footprint left by the success of tea and the consumption culture framing that commodity underscore the history of the tea canister. It is thus in these wider contexts–socioeconomic, societal, cultural, and practical–that we can understand the socio-material significance of this piece.

Neil McKendrick, in his chapter, “The Consumer Revolution of Eighteenth-Century England,” explores the socioeconomic and political development of circumstances which formed the setting for the burgeoning mass consumption of the late 1700’s. McKendrick describes this consumer revolution as a period of great prosperity and rapid economic growth in which emulative spending, coupled with real increases in incomes for the middling classes, resulted in unprecedented conspicuous consumption (3-4). Often, this consumption consisted of luxury goods, such as tea and their complements. In fact, “Tea was ‘singled out [sic] as the apotheosis of luxury spending on needless extravagance by the poor'” (13). Statistics show that “the per capita consumption of tea increased fifteenfold,” and that “tea consumption increased by 97.7 per cent” (13). Luxury products such as this tea canister would thus come to indicate the pervasiveness of this consumer revolution.

Such a unprecedented change in consumption and social life did not go unnoticed. Many responded to such a revolution with alarmist sentiments. The eighteenth-century London moralist John Brown equated the ubiquity of porcelain-wares such as this to the kind of unmanly, tasteless effeminate art that threatened the integrity of the Empire. To Brown, the exoticism of this tea canister would remind him of the plethora of “Porcelain Trees and Birds, Porcelain Men and Beasts, cross-legged Mandarins and Bramins [in which] Every gaudy Chinese Crudity [sic] is adopted into fashionable use, and becomes the Standard of Taste and Elegance” (32). This tea canister would represent for Brown the very “vain, luxurious, and selfish Effeminacy” that undermined the strength and character of English society (20). Because the engravings of this tea canister displays a command of detail in not only the dress and expressions of the figures, but also in illustrating the tea service, we can thus state that this is a luxury good.

Particularly notable to the socio-cultural significance of this tea canister is the presence of an African slave or servant on both portraits. Products associated with Africans likely expressed the fruits of the colonies or of foreign locales, evident in Figure 1 of a “Black Boy Shop Sign” which graced the facades of coffee shops. More importantly, representations of Africans often expressed the power and reach of the Empire. They either symbolize their supposed corrupting influence, as seen in William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress (Figure 2) or, akin to this canister here, emphasized the elevated status of the depicted, as seen in Johan Zoffanny’s The Family of Sir William Young, Baronet (Figure 3). Such figures embodied the exotic other as well as the domestication of the Empire (Koscak).This exoticism thus imbued items such as this tea canister with an air of luxury, which would further drive emulative spending by social emulation (McKendrick 4). As tea became much more accessible, this canister would indicate the very class identity sought to be emulated by new consumers, because it depicts a fashionable lady preparing tea with her black servant. The fact that the figures are outside with a servant highlights the luxury status as well as the exotic implications of tea. That Hancock’s tea canister depicts a tea party suggests the relationship of this lifestyle to the wealthier classes, as pieces like these likely emphasized the luxury quality of tea drinking, making it a popular product for those who wanted to show their class or emulate such a lifestyle.

The utilitarian dimension to this artifact is equally important as its symbolic one. One 1785 pamphlet, The Tea Purchaser’s Guide, presents insight into the material use of tea canisters. According to the chapter, “Best Method of Making Tea,” constant exposure to the air will result in diminished quality (39). In operational terms, a dry tea canister such as this served to keep its tea leaves fresh; it would especially prevent their deterioration during sea-transport (Twining 53, 94). This particular canister was made of soap-rock, thus making it more resistant to boiling water (V&A). This tea canister is also very capaciousness, and so it can hold more tea leaves (V&A). It can thus be surmised that the need to keep more tea fresher was one impetus for the proliferation of tea canisters. The Tea Purchaser’s Guide also commented on the constant dropping of price of tea (6). We can then posit that, in light of McKendrick, this reduction in tea prices, along with its practicality, demonstrates the the wide profusion of tea canisters. It can thus be proven to be true that this Royal Worcester canister embodies the kind of growing commodity consumption McKendrick observes, demonstrating a rapidly increasing, if not flourishing, tea habit.

This Hancock canister is not so different from his other tea caddies, pots, and saucers at time. This canister is in fact an alternate version of a another set with a tea party illustrated on a cup and saucer:

“The Tea Party” Cup and Saucer set

Both display similar scenes designed by Hancock and both were reproduced en masse in factories with high-quality decoration at very little cost using copper transfer-printing plates. And both were made with similar ingredients, such as soaprock, to enhance their material quality.

On the other hand, unlike prior canisters which were smaller and more square or octagonal with a wide cylindrical lip, the Royal Worcester is more bulbous and can hold more tea leaves:

With no models to imitate and seldom mass-produced, these early lightly adorned versions were small and lacked wavy edges and corners and thus did not hold much tea. Later in the century, the larger bulbous-shaped canisters copied by English porcelain factories such as the Worcester canister presented here imitated Chinese vase-like versions made solely for export (V&A). The capaciousness of the later Royal Worcesters attests to the falling price and wider availability of tea.

Bibliography:

Brown, John. “Of the Ruling Manners of the Times.” An Estimate of the Manners and Principles of the Times. (1757-1758): 17-34. PDF.

Hancock, Robert. Tea Canister. Soft-paste porcelain, transfer-printed in black enamel. Royal Worcester. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Museum number: 1448&A-1853. Website.

Hancock, Robert. The Tea Party. Steatitic soft-paste porcelain, thrown and turned, and transfer-printed in black enamel. Royal Worcester. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Museum number: C.93&A-1948. Website.

Kearsley, G. The Tea Purchaser’s Guide; or, the Lady and Gentlemen’s Ten Table and Useful Companion, in the Knowledge and Choice of Teas. (1785): 1-46. PDF.

Koscak, Stephanie. “The British and French Caribbean: Consuming the Exotic.” University of California, Los Angeles. Haines Hall, A2. 4 March 2014. Lecture. Powerpoint.

Lacy, James. “An Essay on the Nature, Use, and Abuse, of Tea, in a Letter to a Lady; with an Account of its Mechanical Operation.” (1722): 1-62. PDF.

McKendrick, Neil. “The Consumer Revolution of Eighteenth-Century England.” The Birth of a Consumer Society. McKendrick, Neil, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb. London: Europa Publications Limited, 1982. 9-33. Print. PDF.

Twining, Richard, the Elder. An Answer to the Second Report of the East India Directors, Respecting the Sale and Prices of Tea. (1785): 1-103. PDF.

Unknown (production). Tea Canister. Salt-glazed stoneware and moulded. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Museum number: 414:958-1885. Website.